Overview

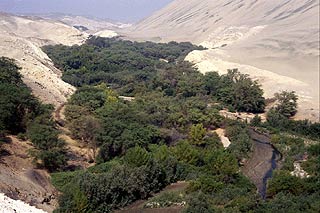

Conducted in the hyper-arid Atacama-Sechura ecoregion, the Habitat Restoration and Sustainable Use of the Southern Peruvian Dry Forest project aims to protect fast-disappearing Prosopis pallida forest relics and combat desertification by working with local communities in Ica, Peru to establish forest reserves and restore a patchwork of small, degraded trial sites. Using native plants reared in local nurseries, the project has carried out restoration activities at several small farming villages and has initiated a number of ambitious community outreach programs designed to foster public support and participation in spite of a social landscape fraught with complexities and competing interests. Practitioners have established an environmental education program at more than 10 schools in Ica; organized two Huarango Festivals to raise public awareness about the benefits of this endangered ecosystem; and helped form a local network to produce and market huarango food products (e.g. flour and syrup) in Lima and abroad. Through these actions, local communities have slowly begun lending their interest and support to project initiatives, and the foundation has been laid for a broad conservation program that will ultimately ensure sustainable local livelihoods and the longevity of a unique forest ecosystem.

Quick Facts

Project Location:

-14.07546, -75.7341811

Geographic Region:

Latin America

Country or Territory:

Peru

Biome:

Desert/Arid Land

Ecosystem:

Other/Mixed

Area being restored:

500 hectares--forest reserve with adjacent trial sites

Project Lead:

Dr William Milliken

Organization Type:

Other

Location

Project Stage:

Implementation

Start Date:

2005-11-18

End Date:

2008-11-18

Primary Causes of Degradation

Agriculture & Livestock, Deforestation, Invasive Species (native or non-native pests, pathogens or plants), Urbanization, Transportation & IndustryDegradation Description

Due to the long history of human occupation in the region, the dry forest on the Peruvian south coast has undergone centuries of deforestation and is now on the verge of extinction as a natural ecosystem. Anthropogenic pressures such as overgrazing, land conversion for agriculture, tree felling for charcoal production, and competition for scarce water resources have severely depleted remaining huarango forest relics, and it is estimated that during the last 30 years, 50,000 hectares have been lost in the Ica region alone–leaving less than 1000 hectares remaining (of which the majority is secondary forest). Adjacent saltmarshes, riparian and xerophytic ecosystems, and coastal lomas with unique endemic flora have also been degraded as a result of these pressures associated with encroaching human populations.

The loss of huarango forest has, in turn, led to widespread soil erosion and salinization throughout the region, and this slow desertification has been further exacerbated by a falling water table. Invasive Tamarix is taking advantage of the changing ecological conditions, and in May 2005, the blanket invasion of sand dunes over fertile land was recorded in areas of recent deforestation on the edge of the Ica Valley floodplain.

Reference Ecosystem Description

The Atacama-Sechura Deserts ecoregion contains approximately 1300 plant species, 60 percent of which are endemic to the Atacama, while 40 percent are endemic to the Sechura. Recently discovered rare and endemic plant species include members of the genus Copiapoa, along with Griselinia carlomunozii and Tillandsia tragophoba. Sixty-eight species are found in both deserts and include: ferns, cone-bearing plants, cacti, and flowering plants that survive by absorbing moisture from fog and dew.

The remaining dry forest on this part of the Peruvian south coast has undergone centuries of deforestation and is nearing extinction as a natural ecosystem. The remaining plant community is characterized by several unusual, highly threatened ecotypes, all of which are now poorly represented. These include: riparian oasis, Andean outwash-fan dry forest, cactus-rich scrub bajadas, ephemeral streams or wadis, coastal lomas, marginal Prosopis coppice dunes, and Prosopis dry forests.

Prosopis pallida (Huarango), a leguminous hardwood, is the dominant arboreal species and provides a number of vital ecosystem services to the larger desert environment. With roots reaching depths of 50-80 metres–the longest roots of any tree in the world–the huarango taps deep stores of water for nourishment and in the process, draws water into more superficial subsoil, effectively creating a source of water for other plant life. Thus, the huarango provides islands of fertility and moisture, helps desalinate the soil, creates favorable microclimates, and represents a key refuge for biodiversity in these desert areas.

The ecoregion is home to more than 150 bird species, including three rare and endemic finches: Slender-billed finch (Xenospingus concolor); Great Inca-finch (Incaspiza pulchra); and Raimondi’s yellow-finch (Sicalis raimondi), and the endemic Pied-crested tit-tyrant (Anairetes reguloides).

Mammals inhabiting the region include the pampas cat (Leopardus pajeros), guanacos (Lama guanicoe), and sea lions (Otaria byronia). A panther was even spotted in the area recently.

Project Goals

To protect remaining relics of huarango dry forest and create buffer zones around them in order to prevent further desertification.

To work cooperatively with local communities in the development of a system for the in situ production and processing of huarango pod products as an option for sustainable use of forested and reforested areas.

Monitoring

The project does not have a monitoring plan.

Stakeholders

Although many of the principal outcomes of the project are focused on the development of realistic methodologies for restoration and the sustainable use of native biodiversity, without a genuine will to pursue these objectives among local community members and authorities–and without the capacity to do so–such methodologies will be of limited value. The project has therefore developed an increasingly strong emphasis on awareness raising and engagement, whilst focusing on enabling a wide range of local organisations and sectors (including, for example, agro-industry) to drive the processes forward with minimal or no requirement for outside financial input. It is believed that this will significantly strengthen the project’s long-term potential.

Description of Project Activities:

The project began with baseline plant surveys, and 800 specimens of over 200 species have now been collected, annotated, and databased (previous inventories for the zone having registered only 128 species). This is the first detailed survey of the flora of the area, providing baseline plant diversity data for the restoration and sustainable use programme.

In June and July 2006, extensive seed collection was undertaken in order to gather a sufficient and representative selection of perennial and annual plants for habitat restoration and educational planting events. A temporary bank of over 30,000 seeds was collected from more than 50 key species, the project focus being the perennial and threatened species, successional annuals and Prosopis landraces.

In August 2006, a large native plant nursery (30 x 9 m) was established in preparation for the ongoing germination and propagation trials. The nursery is located on the grounds of the Faculty of Agronomy of the Universidad San Luis de Gonzaga Ica (UNICA) and is under the direction of local expert Felix Quinteros and a team of students. Several thousand seedlings of 24 key native species have thus far been produced for the following project initiatives: habitat restoration trial sites (1,800 plants); the education programme (1,200); community planting activities (900); the Huarango Festival (2,600); and restoration/conservation actions on independent fundos (2,000).

Three additional on-site native plant nurseries have since been constructed--at Fundo Chapi, Fundo Santa Cruz and Huarangal--for a number of pressing reasons that include: damage to seedlings resulting from transport on very poor roads; a need for wider dissemination of project strategies and goals; and education. Half of the plant nursery in the Andean bajada village of Huarangal was designed to house Cactaceae. Like the huarango forest, this overgrazed and threatened ecotype also supports endemic plant rarities with excellent potential for fruit production and horticulture, as well as high conservation value. Furthermore, the cactus habitat supports two endemic Peruvian birds: cactus canastero and an unidentified subspecies of streaked tit-spinetail.

Because the support and assistance of local communities is so fundamental to the project's success, educational outreach and capacity building have been integrated into all phases of the restoration. An education programme has been established at more than 8 local schools (with plans for continuing expansion) in order to introduce children (ages 3-18) and students (up to 26) to a range of important environmental topics. The programme has centered on tree planting and has used interactive media to communicate the importance of ensuring native biodiversity and ecosystem services. Thus far, well over 3,000 children have participated in the programme, and of these participants, 1,200 have planted a tree. The education programme has now been expanded to include the national network umbrella of the highly successful NGO ANIA and its programme Tierra de los Niños. This relationship will facilitate the nationwide dissemination and exchange of information, and will help expand native planting efforts and increase the capacity of schools and children to play a key role in protecting threatened biodiversity.

As an additional facet of public outreach and education, the first Huarango Festival was organised in Ica in April 2006. The festival was designed to raise local awareness and garner support for conservation actions before the inception of the main project. A second festival, held between 13 and 15 April 2007, was attended by over 3,500 people. More than 2,500 huarango seedlings from threatened productive landrace varieties were distributed during this event, and festival themes included: sustainable use of huarango food products, local ecology and biodiversity, cultural and environmentally focused music, theatre, and story telling. Various food products made from the project's huarango harvest (purchased from a small group of project producers at 80 centavos per kilo to help cover some of the festival costs) were demonstrated for tasting: ice cream, empanadas, cakes, biscuits, flours, coffee, marmalade, chicha (fermented brew) and duck stew. Since these festivals, the regional government has been very supportive and enthusiastic, declaring the 7th of April (a date that coincides with optimum huarango harvest) Dia del Huarango, for official inclusion in the municipal regional calendar.

In December 2006, a honey production trial was begun, wherein 12 hives were brought to the San Pedro trial site by a local producer from Asociación de Apicultores. The trial was intended to test production and provide apicultural training to the community. It was also hoped that the bees would clear up the leaf sugars produced by insect attack, and thus prevent sooty fungus from further damaging the saplings. Due perhaps to climate- and drought-related stress, there was very little nectar flow, and the trial did not prove as successful as hoped. Unfortunately, there are now very few areas were dry forest occurs in sufficient quantity to support honey production exclusively from the forest. In spite of the setbacks experienced, the project has been able to exchange information about nectar-producing native species with the Association, and appropriate species are now being included in trial habitat restoration areas. The project planned to continue pursuing experimental apiculture in San Pedro and Huarangal in August 2007, and if effective apiculture techniques can be established, honey will be sold with Miskihuranga (see below) in collaboration with the community trainees.

Ecological Outcomes Achieved

Eliminate existing threats to the ecosystem:

By December 2006, four habitat restoration trials had been established at degraded sites, and cooperative agreements had been made with the landowners and communities associated with these sites. Two thousand plants are monitored monthly by UNICA and GAP students; ecological observations are made, and such growth indicators as plant height, stem width, canopy area, health, and mortality are noted. Avian biodiversity, activity and numbers are also recorded as indicators of ecological change, whilst pollination and seed dispersal roles are monitored in order to facilitate adaptive management. Reptile and ant observations are also made, as both groups play key roles in soil, seed and succession ecology in arid lands.

At the request of local communities (and with support from additional matching funds), trees and shrubs have also been planted in three community areas outside the habitat restoration trials--Victoria San Joaquin, FONAVI Pueblo Joven, La Banda Palpa--in order to combat desertification. Although not originally part of the programme, these small reforestation projects are relatively inexpensive, both in terms of time and money, and have a significant impact on local engagement in conservation efforts and overall sense of ownership.

One of the initial restoration sites (Fundo Chanca) is situated within an asparagus farm. The ephemeral stream habitat of Chanca is proving to be the key migration corridor and habitat for wildlife moving east-west between the Andes and the riparian habitats of the Rio Ica. A number of rare and endemic species of plants and birds, as well as reptiles, have been recorded in this habitat. The MOU with Fundo Chapi, the largest agro-industrial farm in the area, will provide seven hectares for 5,000 trees and shrubs. This area will provide an ideal location for rigorous comparative evaluation of habitat restoration techniques. Watering will be undertaken by workers from the farm, representing substantial added value for the project. The data from this homogeneous large area of protected land will complement the other four restoration sites, from which hard scientific comparative data are less easy to derive due to the heterogeneity of the conditions.

The management of both farms has shown a developing appreciation of the importance of native biodiversity and as demonstrated its capacity to align production objectives with conservation priorities under such agreements as SGS Eurep GAP. This is particularly significant, as these are among the largest asparagus producers exporting to US and European markets. The large workforce (over 500) on the two farms is allowing wider dissemination of project objectives, for which leaflets and posters are being provided by project staff.

Production in the nurseries has been steady, supplying almost 10,000 plants for project activities and providing a platform for experimental seed management. Germination, propagation and introduction trials have been competed for the 24 key species, including nine varieties of huarango, and over 20,000 huarango seeds have been extracted and stored.

Factors limiting recovery of the ecosystem:

The project has experienced a number of setbacks since its inception, and these have resulted from both social and environmental factors.

Reliable sources of water for irrigation are vital to the project's overall success, but establishing and maintaining water supplies at the habitat restoration trial sites has proven challenging. At the San Pedro site, for example, the use of a well required over 10 community meetings and one workshop in order to gain the necessary trust support. Furthermore, 200m of irrigation canal had to be repaired, and a cement holding tank with a capacity of 10 cubic metres had to be built. The 700 plants at this site are irrigated by hauling 60 litres at a time in a wheelbarrow steered by two people. This job was initially performed by students and staff, but the local family participating in the sustainable management programme eventually assumed responsibility for the weekly watering regime when the cotton harvest ended.

Besides concerns about water, huarango trees have been suffering from a two-fold defoliating plague culminating in severe impact on pod harvests in the Nazca region (from 150 tonnes to virtually nil). The first plague is a virulent defoliating moth, Melipotis aff. indomita. This species is native to the area and historically causes defoliation until controlled by agents such as wasps, birds or cold weather. SENAMI (Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú) has recorded a three-degree increase in minimum average temperature over the last 20 years, and the combination of temperature increase, pesticides, large-scale removal of habitat, and bird trapping are likely factors for the moth's prevalence. However, the caterpillar has been found easy to control through the use of traps. The method requires collection of the hundreds of larvae (that serve as excellent chicken feed) for 3-4 days consecutively from rags left at the base of the trunk (where the larvae roost during the day). The second plague is a Cercydomidyiid gall midge, which has now become a devastating problem. In order to combat these destructive plagues, project staff have begun considering more resistant varieties of Prosopis for propagation and reintroduction.

Another considerable setback suffered by the project was the devastating earthquake that hit the region on 15 August 2007, the strongest felt anywhere in the world since 1990 (Richter 7.9). The quake left over 500 dead, 91,000 with destroyed or uninhabitable houses, and 1,278 badly damaged classrooms. The town of Pisco, 70 km from Ica, was 90% destroyed. These events have thrown much of the Ica region into disorder and affected the Huancavelica - the watershed for Ica. Several members of the project team either lost their houses or had them damaged, and some damage was sustained to wells and irrigation canals used by the project. Funds have been donated from the UK to help with the recovery.

Besides the myriad of intervening environmental factors, local prejudices have also been significant obstacles to achieving project goals. The knowledge of native plants is stigmatised as being associated with poverty. Increasingly, aspirational communities think that if you plant food trees in your home or street, it shows you are still poor. On the other hand, if you plant a tree such as Ficus benjamina - probably the most common house plant in the world - it shows you are part of an affluent neighbourhood and no longer need to grow your own food. Thus helping to raise awareness and change local perceptions will be crucial for the long-term success of the project.

Socio-Economic & Community Outcomes Achieved

Economic vitality and local livelihoods:

Huarangos represent a critical resource for a region supporting a population of over 680,000 people. Not only do they play a pivotal role in ensuring overall ecosystem health by stabilizing the soil, combating salinization, enhancing soil fertility and moisture, and providing habitat for important fauna, they furnish food and a variety of forage products that have contributed to sustainable local livelihoods for thousands of years. With its deep roots, the huarango bears fruit reliably, regardless of erratic river flows--a quality that cannot be overestimated given the region's aridity and unpredictable hydrological patterns. Its bean pods are sweet and nutritious and can be harvested to produce flour and syrup, or eaten straight from the tree. Huarango wood is harder than oak and serves as an excellent construction material and firewood.

Key Lessons Learned

It is increasingly clear that a project such as this–which involves a large number of people from a range of strata of society; draws on several disciplines; addresses highly complex, poorly understood and in some cases sensitive issues; focuses on practical outcomes; and relates directly to livelihoods and policy measures–requires a high degree of flexibility in terms of methodology, logistical considerations, fiscal requirements, and social interaction.

Long-Term Management

Although not originally specified as an output, the project aims to protect biodiversity by helping to establish small, community-protected areas in the remaining fragments of native forest. This is a complex and lengthy process that will require the development of a management plan with sustainable livelihoods options attractive to the local people and a Concession for Conservation (renewable after 40 years) granted by INRENA for each site integrated into the conservation scheme. Three small concessions have been solicited thus far: one in the name of the local community of San Pedro, and one with GAP in Usaca and Tunga (Rio Poroma). The concession for Usaca was approved by INRENA, but in October 2006, the previous owners expressed opposition to the initiative, even though the area had officially reverted to the State following the agrarian reform in 1969. This conflict of interests illustrates the kind of social obstacles against which the project must work if it is to achieve its goals.

For those areas in which restoration has been initiated successfully, project methods and strategies have been adapted to match local necessities and priorities, thereby maximising the likelihood of long-term management in restored areas and uptake of restoration techniques in other contexts. An effort has been made to include species of local economic value, and creative options are being explored for the re-incorporation of huarango resources in the local economy.

The project conducted market research reports for Lima and for local marketing in Ica, and these have been promising. Eight suitable outlets have been identified in Lima for the sale of Prosopis products generated at project sites, and discussions have been held with RBG Kew about highlighting Darwin Project products through the sale of Prosopis syrup in the UK.

There is an expanding group of willing suppliers of huarango fruits in the habitat restoration sites, and also within the proposed conservation concessions. Four local families form the nucleus of this netwok: Alarcon (Nazca), Anchante (Huarangal), Hernandez (Ica) and the workers of San Jorge Fundo. Fruit has also been purchased from two other small producers–for the Festival and for production trials (about 2,000 kg of fruit). Miskyhuaranga, a group of five students at UNICA, is undertaking market research and developing a project under the name Miskihuaranga (Miski means sweet in Quechua). The group will visit and receive training from the Algarrobita and Locuita project in northern Peru, hosted by the University of Puira and El CITE agro-industrial Puira. The aims of the trip are to: (a) learn the techniques of Prosopis fruit management in order to prevent bruchid infestation; (b) note and take photographs of production techniques; (c) interview the communities; and (d) complete a training video for workshops, website and dissemination of CD with the manual.

Two new electric mills–a hammer mill and a spice mill–have been donated by the Instituto Superior Tecnologico Leon de Vivero, in the Tinguiña suburb of Ica, for the processing of collected seed pods. An agreement has been made to allow the project products to be produced seasonally and the Institute to develop its own products while training students to use huarango flour in its adjacent bakery. In May 2007, construction was begun on a small building next to the bakery to house the mills. Profits made from these sales will be reinvested in the sustainable management programme and will also help finance the group.

Sources and Amounts of Funding

Funding for the project has been provided by the Darwin Initiative (£198,214); Rio Tinto PLC; Betty’s and Taylor’s of Harrogate: Trees for Life; and Trees for Cities.

Other Resources

Dr William Milliken, Project Leader

[email protected]

Project description – Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew

http://www.kew.org/scihort/tropamerica/peru/index.htm

Project description – Darwin Intiative

http://darwin.defra.gov.uk/project/15016/

Atacama-Sechura Ecoregion – World Wildlife Fund

http://www.panda.org/about_wwf/where_we_work/ecoregions/atacama_sechura_deserts.cfm