Overview

The Iraqi Marshlands are one of the world’s largest wetland ecosystems and constitute the largest wetland ecosystem in the Middle East and Western Eurasia. The Iraqi Marshlands are a crucial part of intercontinental flyways for migratory birds, support endangered species, and sustain freshwater fisheries, as well as the marine ecosystem of the Persian Gulf. In addition to their ecological importance, these Marshlands are unique from the global perspective of human heritage. The area’s natural beauty is thought to have been the inspiration for the Bible’s description of the Garden of Eden and have been home to indigenous communities for millennia.

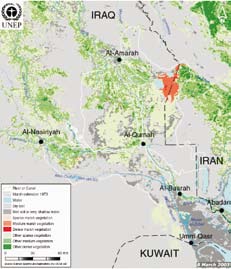

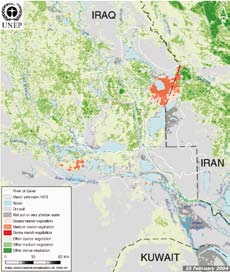

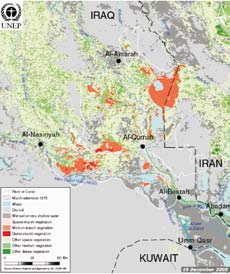

Satellite images of the Marshlands in the early-mid-1970’s showed around 20,000 square kilometers of water surface and wetland vegetation (although diversion of flow has been ongoing through human history in the region especially following the 1950’s). In one generation, the marsh area shrank to a tenth of that size, as did an indigenous population that once numbered a half-million. As an environmental disaster it has been compared in scale to the drying up of the Aral Sea in Central Asia and to the deforestation of the Amazon. “The impact on biodiversity has also been catastrophic,” states a 2004 United Nations study on the marshes. The depletion of the marshes has led to species extinctions with many others at risk. The fisheries, which provided a large share of Iraq’s overall catch, crashed. The effects of the destruction radiate far beyond southern Iraq. No longer cleansed by the marshes, the salty and polluted waters flowing into the Persian Gulf from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are playing havoc with marine life there, including the lucrative shrimp business and coastal fisheries. The marshes were once the permanent habitat for millions of birds and a flyway and staging area for millions more migrating between Siberia and Africa.

The UNEP Marshlands project – “Support for Environmental Management of the Iraqi Marshlands” – is helping Iraqi partners to restore the Marshlands and manage them sustainably. Opportunities for practical cooperation are continually identified and evolving during discussions between representatives of Iraqi authorities (at the national, governorate, and local levels), UN agencies, bilateral organizations, and other stakeholders. UNEP has been involved in coordinating activities of donor countries, as well as those of other agencies, and various organizations involved in the restoration and sustainable management of the Marshlands. UNEP’s responsibilities include coordinating these activities with the work of Iraqi governmental entities. Various entities have endorsed the liaison role of UNEP and its contribution as a key partner, especially in the case of activities concerned with the ecological aspects of marshlands management. The development goal of the Iraqi Marshlands project is to support the sustainable management and restoration of the Iraqi Marshlands. The UNEP Marshlands project has been underway since 2003.

As the former regime ended, people began to open floodgates and break down embankments that had been built to drain the Marshlands. Satellite images and analysis revealed by UNEP in 2006 showed that almost 50 percent of the total Marshlands area has been re-flooded with seasonal fluctuations. Many areas are seeing the return of native plants and animals, including rare and endangered species of birds, mammals, and plants. The rate of restoration is remarkable, considering that reflooding occurred around 2003. Although recovery is not so pronounced in some areas because of elevated salinity and toxicity, many locations seem to be functioning at levels close to those of the natural Al-Hawizeh marsh, and even at historic levels in some areas. Recent field surveys have found a remarkable rate of reestablishment of native macroinvertebrates, macrophytes, fish, and birds in reflooded marshes. Monitoring and evaluation of UNEP pilot projects and the state of the wetlands ecosystem is ongoing with reports and publications continuing to be produced by various research teams and stakeholders.

At least three major questions remain to be answered: (1) Will water supplies needed for marsh restoration be available in the future, given the competition for water from Turkey, Syria, and Iran, as well as competing water uses within Iraq itself? (2) Can the Marsh Arab culture ever be reestablished in any significant way in the restored marshes? (3) Can the landscape connectivity of the marshes be reestablished to maintain species diversity? What is clear is that water supply alone will not be sufficient to fully restore all the marshes, and thus a goal of management should be to establish a series of marshes with connected habitats of sufficient size to maintain a functioning wetland landscape (Richardson and Hussain 2006; Lawler 2005; Richardson and Hussain 2005; UNEP 2006, 2007).

Quick Facts

Project Location:

31.577183, 47.6849007

Geographic Region:

Middle East

Country or Territory:

Iraq

Biome:

Freshwater

Ecosystem:

Freshwater Ponds & Lakes

Area being restored:

20,000 km^2

Organization Type:

Community Group

Project Partners:

UNEP Marshlands project

Location

Project Stage:

Implementation

Start Date:

2003-06-15

End Date:

2010-12-31

Primary Causes of Degradation

Agriculture & Livestock, Fragmentation, Urbanization, Transportation & Industry, OtherDegradation Description

For at least 5000 years, humans have widened and dredged channels, dried and flooded fields, and built reed houses atop artificial islands of reed bundles within the Iraq Marshlands. The lifeblood of this wetland was the spring floods coming down the Euphrates and Tigris river systems with most of this water originating outside Iraq. Beginning in the 1950s, governments began diverting that flow, first by creating natural lakes within Iraq and later by building large dams on both rivers. There are now nearly three dozen major dams, with eight more under construction and a dozen in the planning stages. The result of this half-century of water management has been dramatic. The spring flood is barely noticeable. The maximum flow of the Euphrates during May has dropped by two-thirds since 1974, when dam building began in earnest. Even before the 1991 Gulf War, many experts feared the result would irreparably harm, and eventually destroy, the Iraq marshlands. Severe deforestation from overgrazing upstream, combined with more than a decade of drought in the Middle East, exacerbated the environmental problems to the point at which Minister Latif believes the marshes would soon have been history even without Saddam Hussein’s regime. However, it was Hussein’s regime that delivered the coup de gráce. Part of the Iran-Iraq border runs through the wetlands, and during the 1980s war, both sides built causeways and drained marshy areas for better access to the front. After the first Gulf War and the unsuccessful uprising of Shiite Muslims in the south, the Iraqi government set about draining the remaining marshes. Its goal was to remove the threat of insurgency and replace the marsh culture of fishing and rice production with dry agriculture. Massive dikes and canals were built to divert water from the marshes, quickly turning them to desert (Lawler 2005; Richardson and Hussain 2005; UNEP 2006, 2007).

The sheer scale of the destruction has been likened to biblical proportions. As an environmental disaster it has been compared in scale to the drying up of the Aral Sea in Central Asia and to the deforestation of the Amazon. In one generation, some 20,000 square kilometers of marsh shrank to a tenth of that size, as did a population that once numbered a half-million. The marshes are actually three distinct regions, each with its own particular ecosystem. The once vast Central Marsh, which covered more than 3000 square kilometers in 1973, has shrunk by 97%. Most of what remains are reeds growing in irrigation canals. Another marsh, called al-Hammar, lost 94% of its area, and al-Hawizeh, which borders Iran, is two-thirds smaller than 3 decades ago. Even the Hawr al-Azim Marsh, which is the Iranian extension of al-Hawizeh, is less than half its size due to reductions in water flow from Iraq. As the marshes turned to desert, local peoples fled or were forced from their homes. Left behind were vast salt flats laced with insecticides and landmines. “The impact on biodiversity has also been catastrophic,” states a 2004 United Nations study on the marshes. The depletion of the marshes has led to the extinction of an otter, bandicoot rat, and a long-fingered bat particular to the marshes, and 66 species of water birds and other animals are at risk. The fisheries, which provided a large share of Iraq’s overall catch, crashed. The effects of the destruction radiate far beyond southern Iraq. “The wetlands were like a vast sewage treatment plant for the Euphrates and Tigris system,” says Hassan Partow, who helped write the U.N. report, “they were the kidneys”, without them, the patient is imperiled. No longer cleansed by the marshes, the salty and polluted waters flowing into the Persian Gulf from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are playing havoc with marine life there, including the lucrative shrimp business and coastal fisheries. The marshes were once the permanent habitat for millions of birds and a flyway and staging area for millions more migrating between Siberia and Africa (Lawler 2005; Richardson et al. 2005).

Reference Ecosystem Description

The Iraqi Marshlands are one of the world’s largest wetland ecosystems and constitute the largest wetland ecosystem in the Middle East and Western Eurasia. Satellite images of the Marshlands in the early-mid-1970’s show around 20,000 square kilometers of water surface and wetland vegetation (although diversion of flow has been ongoing through human history in the region especially following the 1950’s). The Marshlands, consisted of interconnected lakes, mudflats and wetlands in the lower part of the Tigris-Euphrates basin of Iraq and Iran. The Iraq Marshlands are a crucial part of intercontinental flyways for migratory birds, support endangered species, and sustain freshwater fisheries, as well as the marine ecosystem of the Persian Gulf. In addition to their ecological importance, these Marshlands are unique from the global perspective of human heritage. They have been home to indigenous communities for millennia (Lawler 2005; Richardson and Hussain 2005; UNEP 2006, 2007).

Project Goals

The development goal of the Iraqi Marshlands project is to support the sustainable management and restoration of the Iraqi Marshlands (UNEP 2007), with the following immediate objectives: (1) to monitor and assess baseline characteristics of the marshland conditions, to provide objective and up-to-date information, and to disseminate tools needed for assessment and management, (2) to build capacity of Iraqi decision makers and community representatives on aspects of marshland management, including: policy and institutional aspects, technical subjects, and analytical tools, (3) to identify EST options that are suitable for immediate provision of drinking water and sanitation, as well as wetland management, and to implement them on a pilot basis, (4) to identify needs for additional strategy formulation and coordination for the development of longer term marshland management plan, based on pilot results and

cross-sectoral dialogue.

Monitoring

Monitoring Details:

Monitoring is continuing to assess the recovery, and additional efforts are now being focused on measuring plant and fish production, changes in water quality, and specific populations of rare and endangered species. Unfortunately, no research is under way to assess how agriculture and the marshes can share scarce water supplies, to identify toxic problem areas, to study the problems of insecticide use by local fishermen, or to conduct a complete survey of the marshes to determine optimum restoration sites, because of limited funding and increased violence in the area. However, the long-term future of the former Garden of Eden really depends on the willingness of Iraq’s government to commit sufficient water for marsh restoration and to designate specific areas as national wetland reserves. Political pressure from the international community to maintain water supplies flowing into Iraq will also be critical to the restoration of the marshes (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Following the end of this pilot project in 2009, UNEP and UNESCO established a joint project titled "Natural and Cultural Management of the Iraqi Marshlands" that builds upon the successful model of the pilot. UNEP notes that previous monitoring of water quality, biodiversity, and vegetative cover have provided a snapshot of historical environmental conditions. Project leaders have transferred the necessary equipment to Iraqi stakeholders and provided training in order to allow continued monitoring.

The project aims to guide and support Iraqi stakeholders through the development of a sustainable management plan for the Iraqi Marshlands that complies with the World Heritage inscription process. Management has shifted from short-term post-conflict development to long-term re-establishment initiatives. For more information, visit: http://www.unep.or.jp/ietc/IraqWH/index.html.

Start date, including baseline data collection:

2004

End Date:

Continuous

Stakeholders

Iraqi authorities and donor governments have engaged in dialogue and coordination activities concerned with the restoration and sustainable management of the Marshlands since 2003. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and other UN groups play an increasingly active role in promoting such activities. Opportunities for practical cooperation are continually identified and evolving during discussions between representatives of Iraqi authorities (at the national, governorate, and local levels), UN agencies, bilateral organizations, and other stakeholders. UNEP has been involved in coordinating activities of donor countries (including Canada, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom and United States), as well as those of the World Bank, other UN agencies, and various organizations involved in the restoration and sustainable management of the Marshlands. UNEP’s responsibilities include coordinating these activities with the work of Iraqi ministries and other relevant Iraqi bodies including the Ministry of Environment (MOE), Ministry of Water Resources (MOWR), and the Ministry of Municipalities and Public Works (MMPW). Various entities have endorsed the liaison role of UNEP and its contribution as a key partner, especially in the case of activities concerned with the ecological aspects of Marshlands management.

Other agencies and non-governmental organizations involved in aspects of the restoration of the Iraqi Marshlands and/or the people and culture associated with this area include groups such as Eden Again, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Center for Restoration of the Iraqi Marshes (CRIM) (an organization of several Iraqi ministries). Universities and scientists both within and outside of Iraq have played a role in the various specific projects surrounding the restoration of the Marshlands and their native inhabitants. Iraqi communities, community leaders and their citizens, especially those surrounding the project region, have played an integral role in the restoration, planning, and implementation of project aspects (Lawler 2005; Richardson et al. 2005; UNEP 2006).

Description of Project Activities:

Extensive ecological damage to the Iraqi Marshlands area, with the accompanying displacement of much of the indigenous population, was identified by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the United Nations/World Bank Needs Assessment Initiative for the Reconstruction of Iraq as one of the country's major environmental and humanitarian disasters. In 2001, UNEP alerted the international community to the destruction of the Marshlands when it released satellite images showing that 90 percent of the Marshlands had already been lost. Experts feared that the Marshlands ecosystems would be completely lost within three to five years unless urgent action was taken. UNEP has continued to be the leading agency reporting on the condition of the Marshlands. As the former regime ended, people began to open floodgates and break down embankments that had been built to drain the Marshlands. Re-flooding has since occurred in some, but not all, areas. Satellite images and analysis by UNEP show that approximately up to 50 percent of the total Marshlands area has been re-flooded with seasonal fluctuations (UNEP 2006).

Water quality problems include contamination by pesticides, by untreated industrial discharge, and by sewage originating upstream. Pollution and the high salinity levels of both water and soil are in part due to the limited flow of water through the Marshlands. A 2003 UN inter-agency assessment and a public health survey conducted by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) indicated that safe drinking water had become the inhabitants' most critical need. While some people could buy tanker water, many others had no choice but to drink untreated, unfiltered marsh water. UNEP's dialogues with the local communities and government officials confirmed that provision of safe drinking water was the number one priority for the local population. To protect human health and livelihoods and to preserve the area's ecosystems and biodiversity, the Iraqi authorities included water quality and Marshlands management on the priority list for reconstruction under the United Nations Development Group (UNDG) Iraq Trust Fund and made direct appeals to donor governments for assistance (UNEP 2006).

In July 2004, the Iraq Trust Fund Steering Committee of the United Nations Development Group (UNDG) approved the Marshlands project and implementation began the same year. Additional funding has been provided by numerous sources. UNEP was requested to play a coordinating role in the Marshlands management activities of various UN and bilateral agencies, and of Iraqi institutions. The International Environmental Technology Centre (IETC), located in Japan, is carrying out project implementation. IETC promotes and implements Environmentally Sound Technologies (ESTs), including management systems, for: disaster prevention; production and consumption; water and sanitation. IETC is part of UNEP's Division of Technology, Industry and Economics (UNEP DTIE) (UNEP 2006).

Phase I (2004 - ) of the Marshlands project is being implemented within the framework of the UNDG Iraq Trust Fund. Work during Phase I focuses on: safe drinking water; sanitation and wastewater treatment; and wetland and water quality management. There is a strong emphasis on providing Iraqi partners with specialized training. Continuous information exchange takes place with Iraqi stakeholders, including ministry representatives, professionals associated with academic institutions, and community leaders. The Arabic-English Marshlands Information Network (MIN) is a web-based platform used to share data, analysis, and analytical tools. Websites created by Iraqi partner institutions exist in both languages. A number of individuals in ministries, governorates, and non-governmental bodies are using this platform. To foster greater environmental awareness among Marshland inhabitants, UNEP was also able to support three community level initiatives in southern Iraq. The initiatives were proposed, implemented, and reported on by community members. Monitoring of the initiatives was overseen through a unique collaboration among the local Environment Directorates, the Governing Councils, and the Arab Marshlands Councils (UNEP 2006).

Phase II (2006 - ) is now running in parallel with Phase I and building on its success. Planning for Phase II was carried out with the Iraqi Ministries of Environment (MOE), Water Resources (MOWR), and Municipalities and Public Works (MMPW). Phase II-A: strategy formulation and coordination; baseline data collection and assessment; capacity building. Activities supported include: coordinated data collection and analysis of water, environmental, and socio-economic parameters; expanded use of the MIN to share and manage data; provision of additional hardware, software, and training. Phase II-B: drinking water provision and water quality management; pilot implementation and community level awareness; and awareness raising. Activities supported include: a pilot project for drinking water provision in another community; an additional training course; an International Workshop, to be held in Kyoto in December 2006; continued initiatives at local community level; the update of awareness raising materials (UNEP 2006).

The involvement of Iraqi communities in decision-making on projects that directly impact them is growing. Meaningful improvement of the Marshlands depends on community support and initiatives. UNEP therefore introduced small-scale community level initiatives in the three southern governorates. Example 1: The Marsh Arab Council of Thi-Qar undertook an initiative to raise awareness of the dangers of fishing using poison within the Marshlands Environment. To address this important issue, the Marsh Arab Council launched a public awareness campaign. Short training courses were given to tribal chiefs and religious leaders. The Marsh Arab Council and Ministry of Environment sought the assistance of the newly trained tribal chiefs and religious leaders to help explain the adverse affects associated with fishing by poison to local fishermen and their families. The overall rationale behind the campaign was to begin to create an atmosphere in which using poison for fishing will become unacceptable within Marshlands society and will lead to the elimination of this practice. Example 2: The initiative to Develop an Understanding Among Marshland Residents in Missan on the Importance of the Marshland Ecosystem had two components, the second was a training course for young people, on the importance of the Marshlands environment. The purpose of this course was to stimulate interest in environmental issues and to begin the process of viewing the Marshlands as a common good requiring trans-generational management (UNEP 2006).

Beginning in 2004, a series of ten training courses within Phase I and two additional courses within Phase II were organized by IETC, responding to needs identified by relevant Iraqi institutions. Each course was designed to enhance Iraqi participants' knowledge of developments in areas such as environmental policy and institutional aspects; technical capability; and data and IT management. These courses supported practical capacity building, with linkages to pilot project implementation, policy analysis and development, and data management. Courses consisted of lectures in English and Arabic, demonstrations, and group exercises. Participants took an active part in discussions and other activities. Most courses included site visits. Training manuals were prepared in Arabic and English. Course material was organized under three headings: policy and institutional; technical; and data management and analysis. The training courses corresponded to elements of UNEP's Marshlands project. Courses were designed using the "train the trainers" model. I n this way, participants can pass on the knowledge acquired to their colleagues. UNEP provides support for "secondary training," including provision of training materials and funding for course organization. Five secondary courses have been organized in Iraq so far by the Ministry of Environment (MOE), the Ministry of Water Resources (MOWR), and the Universities of Basrah and Thi-Qar. Trained personnel from the earlier courses helped to organize and deliver lectures for the secondary training (UNEP 2006).

In June 2006, as a Phase II-A activity, IETC organized a meeting with technical experts from the Iraqi Ministries of Environment (MOE), Water Resources (MOWR), and Municipalities and Public Works (MMPW). The meeting's overall purpose was: to assist Iraqi ministries in effectively analyzing, presenting, and sharing available data using the Marshlands Information Network (MIN); to develop a strategy for initial data collection efforts concerning basic demographic and socioeconomic data and solid waste management in the Marshlands. At the meeting, Iraqi officials (in collaboration with IETC staff) accomplished the following: developed plans for each ministry to coordinate data collection inside the Marshlands, to continue the upkeep and updating of the MIN, to further develop effective reports using existing and forthcoming data, and to expand use of the MIN as a tool to share and manage data; used existing data provided by ministries as examples of how to analyze, share, manage, and upload effective reports; completed reorganization and streamlining of the MIN site structure for the ministries' MIN web sites. The Marshlands Information Network (MIN) provides a forum for information and data sharing. All institutions taking part in the Marshlands' restoration and management have access to this cost-effective, internet-based tool through a version of the Environmentally Sound Technology Information System (ESTIS) in Arabic. ESTIS is an innovative, multi-language e-service developed by IETC in 2003 (UNEP 2006).

Monitoring and evaluation of UNEP pilot projects and the state of the wetlands ecosystem is ongoing with reports and publications continuing to be produced by various research teams and stakeholders. One example is a recent study by Richardson and Hussain (2006) that sought to assess the level of marsh restoration. The vast amount of former marsh area prevented the authors from completing a detailed ecological analysis of all the reflooded sites. The researchers covered the three historic marsh areas (Central, Al-Hawizeh, and Al-Hammar), we selected four very large marshes: Al-Hawizeh, the only natural remaining marsh on the Iranian border; the eastern Al-Hammar marsh; Abu Zarag (western Central marsh); and Suq Al-Shuyukh (western Al-Hammar). From 2003 until 2005, the researchers monitored water quality, water depth and transparency, soil chemistry conditions, and ecological indicators of plant and algal productivity; and surveyed the numbers and species of birds, fish, and macroinvertebrate populations (for a detailed analysis of the field and laboratory chemistry methods and statistical analyses used in this article, see Richardson et al. 2005 and others). This original work was done in conjunction with Iraqi scientists to assess the ecological and environmental conditions present where the dominant flora and fauna in the natural Al-Hawizeh still existed and to compare these conditions with those of three marshes reflooded in 2003. To provide an estimate of overall ecosystem health, the researchers completed an ecosystem functional assessment (EFA) to determine restoration progress to date and to establish how the newly reflooded marshes were functioning compared with the natural marsh and with historical values.

In the EFA method, indicators of ecosystem function are grouped into five ecosystem-level functional categories: hydrologic flux and storage, biological productivity, biogeo-chemical cycling and storage, decomposition, and community/wildlife habitat. Next, a carefully chosen set of variables representing these five functional categories are selected as key indicators to be measured in the affected ecosystems and in a set of reference ecosystems. Key indicator values obtained in the field from the affected ecosystem are scaled against those from reference ecosystems to determine whether there are significant shifts in these indicators. The EFA analysis of the marshes was somewhat compromised in terms of the collection of the most appropriate key indicators for each function because of the difficulty of sampling in remote and dangerous areas of Iraq. Thus, these estimates of ecosystem health are less quantitative than a standard EFA.

Ecological Outcomes Achieved

Eliminate existing threats to the ecosystem:

Satellite images and analysis revealed by UNEP in 2006 showed that almost 50 percent of the total Marshlands area has been re-flooded with seasonal fluctuations. Many areas are seeing the return of native plants and animals, including rare and endangered species of birds, mammals, and plants. The rate of restoration is remarkable, considering that reflooding occurred around 2003. Although recovery is not so pronounced in some areas because of elevated salinity and toxicity, many locations seem to be functioning at levels close to those of the natural Al-Hawizeh marsh, and even at historic levels in some areas. Recent field surveys have found a remarkable rate of reestablishment of native macroinvertebrates, macrophytes, fish, and birds in reflooded marshes (UNEP 2007; Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Factors limiting recovery of the ecosystem:

Uncontrolled releases of Tigris and Euphrates River waters after the 2003 war have partially restored some former marsh areas in southern Iraq, but restoration is failing in others because of high soil and water salinities. Although the uncontrolled reflooding is welcome news, it presents potential problems and challenges regarding the quality of water including: the release of toxins from reflooded soils that are contaminated with chemicals, mines, and military ordnance; flooding of local villages and farms now developed on the edges of formerly drained marshes; and a false sense of security regarding the volume of water that will be available to restore the marshes in future years. Of concern is the potential for the bioaccumulation of toxic elements such as Se up the food chain, which could result in severe toxic effects in the marshes for higher trophic levels. Finally, it is unknown if sufficient water supplies can be made available, especially in drought years, to maintain long-term successful marsh restoration over large areas (Richardson et al. 2005).

Water:

Approximately 70% of the water entering Iraq comes from river flow controlled by Turkey, Iran, and Syria. Annual rainfall only averages around 10 cm in southern Iraq, while evapotranspiration rates can reach nearly 200 cm. Groundwater sources are highly saline and not useful for drinking or irrigation without expensive treatment. A series of major trans-boundary water issues include the completion of the massive Southeastern Anatolia Irrigation Project (GAP) in Turkey, with 22 dams supplying irrigation water to 1.7 million hectares (ha) of agricultural land, and the Tabqa Dam project in Syria, supplying water to 345,000 ha of irrigated land. In addition, the dike being built by Iran to cut off the Iranian water supply to the Iraqi portion of the Al-Hawizeh is nearing completion (Richardson et al. 2005). The water from the Iranian project reportedly will be sold to Kuwait, which suffers severe freshwater supply problems. The AtatÁ¼rk Dam, built in Turkey as part of GAP in 1998, can store more than the 30.7 billion cubic meters (m3) of water that flows annually through the Euphrates from Turkey into Iraq; this dam alone could almost dry up the Euphrates (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

There are now nearly three dozen major dams, with eight more under construction and a dozen in the planning stages. Turkey alone can store up to 91 billion cubic meters of water and will need more to irrigate its dry eastern provinces. Iraq and Syria can store as much as 23 billion cubic meters. The 2003 war and its aftermath halted plans to build additional dams in Iraq--there are currently a dozen large ones--but Iran recently embarked on a major dam-building effort on tributaries of the Tigris. The result of this has been the spring flood is barely noticeable. The maximum flow of the Euphrates during May has dropped by two-thirds since 1974, when dam building began in earnest. Severe deforestation from overgrazing upstream, combined with more than a decade of drought in the Middle East, exacerbated the environmental problems to the point at which Minister Latif believes the marshes would soon have been history "even without Saddam." (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Projected future demands for water for agriculture and other human uses are enormous, with estimates of Iraq's water needs close to 95 billion m^3 by 2020; however, only 48 billion m^3 are estimated to be available after Turkey and Syria complete their dams. It is estimated that to restore 10,000 km^2 of marshes will require from 20 billion to 30 billion m^3 of water, nearly 50% of Iraq's available water after the completion of the water projects and dams in Turkey and Syria. It is clear from these estimates that there will not be enough water to meet the projected needs of Iraq's population and agriculture; thus, the marshes will be in direct competition for water. This will be especially true in drought years. However, some of the used agricultural water may be adequate for use in the marshes, but that has not been studied in terms of elevated salinity and long-term nutrient and pesticide effects (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Given the competition for water among cities, agriculture, and marshes, serious shortages will exist, especially in dry years. Another problem will arise when areas that have been partially restored after water has been released into them have their water supplies cut off during drought-year shortages. This will result in further destruction of soil structure and overall loss of biota. To prevent this, a set minimum yearly water allocation should be made to the most viable former marsh areas. Bottom line, given the fast pace of dam construction in countries upstream and the possibility of another drought, though, renewed desertification is likely. In Iraq, the Center for Restoration of Iraqi Marshes will need to work closely with all the ministries, especially the Ministry of Water Resources and the Ministry of Agriculture, to maintain future water supplies for the marshes. The wild card in this plan is the Ministry of Oil, which has not actively participated in the marsh restoration program; vast quantities of oil are reported to exist under former marsh areas in southern Iraq (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Water Quality:

It is not clearly understood by many engineers and water managers that reflooding does not equal wetland restoration. While the presence of adequate water is critical to marsh restoration, the restoration of wetland functions requires also the proper water hydroperiod (period of time water is at or near the surface), hydropattern (distribution of water over the landscape), and good water quality. These conditions are complex in nature. Restoration projects that do not take this complexity into account can at first seem to be successful, but they are later recognized as failures because conditions promoting important ecosystem functions have not been adequately restored. Water flow through the year in some areas kept the salinity concentrations low and prevented the buildup of potentially toxic elements, such as selenium and salts, that was seen in the diked areas of Al-Sanaf. Now, dams, dikes, and canals prevent the overflow of water at the marsh edges, thus reducing the historical inundation pattern of the marshes. The restricted water outflows in the Al-Sanaf, coupled with high regional evapotranspiration rates, have resulted in extremely high ion concentrations, pH, and TDS, values similar to those measured in highly salinized portions of the Jordan River. Results from Al-Sanaf suggest that simply adding water to former marshes without providing for continual flushing will result in excessive salinity and toxicity problems (Richardson and Hussain 2006; Richardson et al. 2005).

Toxic levels of sulfides and salts have been reported in a few areas of the reflooded marshes. Minefields exist throughout the marshes along the border of Iran, and a number of villages were flooded by the destruction of dikes and dams. Marsh restoration has been further complicated by the construction of more than 30 dams and several thousand kilometers of dikes in Iraq during the past 30 years. This infrastructure has resulted in the retention of large volumes of water in the central portions of Iraq for cities and agriculture, as well as in the reduction of new sediment accumulation in the marshes. During the past two years, high snowmelt from the mountains of Turkey and Iran has resulted in near record flows on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, resulting in vast amounts of excess water being available for re-flooding of the marshes, but it is unknown how long this pattern of increased water release will last. Regardless, restoration may be difficult in some localized areas, because soil conditions and water quality in the drained and diked (as compared with the reflooded and natural) marshes clearly demonstrated massive shifts in ion chemistry and structure. For example, many areas of the marshes were severely burned after drainage. The intensity of the burns in some areas, with high surface organic matter covering sulfidic pyrite soils beneath, resulted in soils being greatly altered chemically and then exposed to oxygen for decades of draining, resulting in the formation of sulfuric acid. These highly oxidizing conditions liberate iron (Fe), Ca, Mg, and trace elements like copper as well as producing toxic conditions and sodic or calcic soils when reflooded. Moreover, X-ray scanning electron microscopy work suggests that the burned soils where iron sulfide (FeS2) has been converted to iron oxide maghermite (Fe2O3) now have a texture like ceramic, meaning that the soil will not rewet and cannot support plant life. The soil chemistry analysis results suggest that reflooded and drained marsh areas can be restored, but some locations will have excessive salt accumulation problems, toxic elements, and severe water quality degradation, with a concomitant loss of native marsh vegetation. It is imperative that these areas be identified so that the limited water supplies can be used to restore those areas with the most promise for full restoration (Richardson and Hussain 2006; Richardson et al. 2005).

Connectivity:

Wetland habitat fragmentation (disconnected patches), one of the most commonly cited causes of species extinction, and ensuing loss of biological diversity are quite evident when surveying the distance between reflooded marshes. The sparsely vegetated reflooded areas are very scattered compared with the contiguous wetland landscape found in 1973. In addition, many of the former water flow connections between marsh patches are now blocked by dikes and canals. The Al-Hawizeh, the only remaining natural marsh, is under current threat from a large Iranian dike. Landscape connectivity, the inverse of landscape fragmentation, is now considerably reduced, which can have significant effects on population survival and metapopulation dynamics for macroinvertebrates, fish, amphibians, and even plants (Richardson and Hussain 2006; Richardson et al. 2005).

Politics and People:

Coming up with a common vision--and financing--in an unstable nation may prove even harder than collecting data. "This is a scientifically difficult and tremendously complex effort," says Edwin Theriot, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers official who has advised the Iraqi government. "We're having difficulties with the Everglades and in Louisiana--and we're supposed to have all the resources we need." It is clear the political climate in Iraq is still volatile. In fact, for at least one study, Iraqi scientists declined to be interviewed about their work, fearing reprisals from insurgents - but one such scientist went on record as saying data collection is ongoing. Although he also stated that researchers are still harassed at times by the bandits who roam the region.

One interesting turn following the fall of last regime are that many believe the marsh people are not interested in restoring all the marshes, wanting some restored and some left dry for agriculture. Peter Reiff, an anthropologist who works on the marsh issue as a USAID contractor, notes that local Marsh Arabs have abandoned their old way of life cultivating rice and using water buffalo: "They are becoming farmers, and they get better returns with sheep, wheat, and cattle." And he accuses outsiders such as Alwash of possessing "a wistfulness about the marshes that is almost romantic. You are not going to make this into an ethnographic museum." Iraqis themselves are divided. Minister Latif says he is "not very keen on the word "restoration"--restoring does not help the population." He favors a plan that focuses on health, education, and transportation needs. And the long-suffering local people appear to want it all. During two recent conferences on the marshes held in southern Iraq, participants urged that the wetlands be restored--and that new schools, clinics, and roads be built to lift them out of their dire poverty. CRIM is supposed to bring all these disparate parties together. But some doubt it has the political and financial muscle to do so. "CRIM is understaffed, under-resourced, undertrained, if well-intentioned," says one foreign scientist involved in its creation. And negotiating a deal with Turkey, Syria, and Iran on water rights--a crucial element in any restoration plan--poses a daunting diplomatic challenge. "It is quite obvious that there isn't enough water to restore all the desiccated marshes," says Farhan. Even the enthusiastic Alwash--who calls the Eden Again project "his mistress"--acknowledges that full restoration is unrealistic, given the constraints of water, money, and political will (Lawler 2005).

And on"¦

What is clear is that water supply alone will not be sufficient to fully restore all the marshes. Iraq must also use water more efficiently and cut waste if the country is to have enough water to meet its future needs. For example, the continued use of the ancient method of flooding vast agricultural fields from open ditches, coupled with extremely high evapotranspiration rates, results in massive losses of water to the atmosphere and increased soil salinity problems. Modern drip irrigation approaches used throughout other parts of the Middle East need to be employed to preserve Iraq's dwindling water supply.

Monitoring is continuing, unfortunately no research is under way to assess how agriculture and the marshes can share scarce water supplies, to identify toxic problem areas, to study the problems of insecticide use by local fishermen, or to conduct a complete survey of the marshes to determine optimum restoration sites, because of limited funding and increased violence in the area. However, the long-term future of the former Garden of Eden really depends on the willingness of Iraq's government to commit sufficient water for marsh restoration and to designate specific areas as national wetland reserves. Political pressure from the international community to maintain water supplies flowing into Iraq will also be critical to the restoration of the marshes (Richardson and Hussain 2006; Richardson et al. 2005).

Socio-Economic & Community Outcomes Achieved

Economic vitality and local livelihoods:

As the former regime ended, people began to open floodgates and break down embankments that had been built to drain the Marshlands. Re-flooding has since occurred in some, but not all, areas. Satellite images and analysis by UNEP show that approximately up to 50 percent of the total Marshlands area has been re-flooded with seasonal fluctuations. To protect human health and livelihoods and to preserve the area's ecosystems and biodiversity, the Iraqi authorities included water quality and Marshlands management on the priority list for reconstruction under the United Nations Development Group (UNDG) Iraq Trust Fund and made direct appeals to donor governments for assistance.

With both phases of the UNEP Marshlands Project underway, the following benefits can be identified: * ESTs are being introduced and implemented, making use of Iraqi expertise: up to 22,000 people in six pilot communities (Al-Kirmashiya, Badir Al-Rumaidh, Al-Masahab, Al-Jeweber, Al-Hadam, and Al Sewelmat) have access to safe drinking water supplied by common distribution taps; by the middle of 2006, 23 kilometres of water distribution pipes and 86 common distribution taps had been installed; partly because drinking water was made available through this project, people are returning to pilot site areas; as stability returns, possibilities for finding employment and rebuilding life in the marsh ecosystem are increasing; a sanitation system pilot project is being implemented in the community of Al-Chibayish. The EST, constructed wetlands, aims to serve approximately 170 inhabitants, who face health hazards from discharges of untreated wastewater to a nearby canal; wetland rehabilitation and reconstruction initiatives are being implemented in cooperation with the Center for the Restoration of Iraqi Marshlands of the Ministry of Water Resources (MOWR). * Input is being provided for a long-term management plan to benefit people and ecosystems in Southern Iraq. This input includes: experience with suitable management options; recognition of local communities as stakeholders; assessment of policy and institutional needs; identification of (and engagement with) evolving and emerging Iraqi institutions associated with marshlands management; provision of analyzed data, gathered through water quality testing, satellite image analysis, and remote sensing. * The capacity and knowledge of Iraqi decision-makers, technical experts, and community members are being enhanced. Policy and institutional elements, technical knowledge, community engagement, and analytical methods are among the aspects being addressed. * Employment opportunities related to assessment, pilot applications, awareness raising, and monitoring are being developed at professional and community levels.

Using Environmentally Sound Technologies (ESTs), safe drinking water is being provided to the inhabitants of six pilot Marshlands communities and a sanitation system ("constructed wetlands") is being introduced in another community. The EST pilot projects were planned and carried out with full stakeholder involvement. In view of their desperate need for safe drinking water, residents of the Marshlands have responded overall with great satisfaction. Previously, inhabitants drank unclean marsh water (associated with a high rate of disease) or purchased drinking water trucked in from distant locations. In these pilot communities there is increased optimism and a desire to renew life within the Marshlands. The presence of the pilot water treatment plants has encouraged many households to return and begin rebuilding their lives here. This is reflected in increased livestock numbers, contributing in turn to the production of dairy products, reed crafts, and other items that can be sold in market centres. Water treatment plant operators are satisfied with the equipment's ease of operation. Extensive training is not required in order to operate it. The project faced many challenges and constraints at the outset, principally due to lack of understanding of the project's potential health and economic benefits. However, the timely completion of pilot projects supplying safe water is having a tremendous impact with respect to building confidence in this project within communities.

Meaningful improvement of the Marshlands depends on community support and initiatives. UNEP therefore introduced small-scale community level initiatives in the three southern governorates. Beginning in 2004, a series of ten training courses within Phase I and two additional courses within Phase II were organized by IETC, responding to needs identified by relevant Iraqi institutions. Courses were designed using the "train the trainers" model. In this way, participants can pass on the knowledge acquired to their colleagues (UNEP 2006).

A functioning marsh ecosystem will undoubtedly benefit the people of Iraq in numerous direct and indirect ways. Release of water in many areas is resulting in the return of native plants and animals, including rare and endangered species of birds, mammals, and plants. The rate of restoration is remarkable, considering that reflooding occurred in 2003. The marshes were once famous for their biodiversity and cultural richness. They were the permanent habitat for millions of birds and a flyway for millions more migrating between Siberia and Africa. More than 80 bird species were found in the marshes in the last complete census in the 1970s. Populations of rare species which had been thought close to extinction, were recently seen in a winter bird survey. Coastal fish populations in the Persian Gulf used the marshlands for spawning migrations, and the marshes also served as nursery grounds for penaeid shrimp and numerous marine fish species. The return of marsh areas will likely help restore this function. This also goes toward the marshlands serving as a natural filter for waste and other pollutants in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, thus protecting the Persian Gulf.

Some of the former Marsh Arabs have chosen to return to the marshes. On several trips researchers noted an increasing number of families returning to Suq Al-Shuyukh and Al-Hammar. When asked why they returned, they simply stated that they had no other place to go and that the marsh provides some protection and food. Moreover, many of the former Marsh Arabs are now successfully farming on the edge of the marshes. For the first time in their lives, many are making a meager living by farming wheat, rice, and barley (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Key Lessons Learned

The restoration of southern Iraq’s Mesopotamian marshes is now a giant ecosystem-level experiment. Uncontrolled release of water in many areas is resulting in the return of native plants and animals, including rare and endangered species of birds, mammals, and plants. The rate of restoration is remarkable, considering that reflooding occurred around 2003. Although recovery is not so pronounced in some areas because of elevated salinity and toxicity, many locations seem to be functioning at levels close to those of the natural Al-Hawizeh marsh, and even at historic levels in some areas. At least three major questions remain to be answered: (1) Will water supplies needed for marsh restoration be available in the future, given the competition for water from Turkey, Syria, and Iran, as well as competing water uses within Iraq itself? (2) Can the Marsh Arab culture ever be reestablished in any significant way in the restored marshes? (3) Can the landscape connectivity of the marshes be reestablished to maintain species diversity?

What is clear is that water supply alone will not be sufficient to fully restore all the marshes, and thus a goal of management should be to establish a series of marshes with connected habitats of sufficient size to maintain a functioning wetland landscape. Iraq must also use water more efficiently and cut waste if the country is to have enough water to meet its future needs. For example, the continued use of the ancient method of flooding vast agricultural fields from open ditches, coupled with extremely high evapotranspiration rates, results in massive losses of water to the atmosphere and increased soil salinity problems. Modern drip irrigation approaches used throughout other parts of the Middle East need to be employed to preserve Iraq’s dwindling water supply.

Monitoring is continuing to assess the recovery, and additional efforts are now being focused on measuring plant and fish production, changes in water quality, and specific populations of rare and endangered species. Unfortunately, no research is under way to assess how agriculture and the marshes can share scarce water supplies, to identify toxic problem areas, to study the problems of insecticide use by local fishermen, or to conduct a complete survey of the marshes to determine optimum restoration sites, because of limited funding and increased violence in the area. However, the long-term future of the former Garden of Eden really depends on the willingness of Iraq’s government to commit sufficient water for marsh restoration and to designate specific areas as national wetland reserves. Political pressure from the international community to maintain water supplies flowing into Iraq will also be critical to the restoration of the marshes (Richardson and Hussain 2006).

Long-Term Management

Input is being provided for a long-term management plan to benefit people and ecosystems in Southern Iraq. This input includes: experience with suitable management options; recognition of local communities as stakeholders; assessment of policy and institution needs; identification of (and engagement with) evolving and emerging Iraqi institutions associated with marshlands management; and provision of analyzed data, gathered through water quality testing, satellite image analysis, and remote sensing (UNEP 2006, 2007).

Sources and Amounts of Funding

$30 million + USD The total international funding to date for marsh restoration is slightly in excess of $30 million (at least $11 million from Japan) (Richardson and Hussain 2006; UNEP 2006). UNEP has been involved in coordinating activities of donor countries (including Canada, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States), as well as those of the World Bank, other UN agencies, and various organizations involved in the restoration and sustainable management of the Marshlands.

Other Resources

Contacts: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, Kenya; Tel: ++254-(0)20-762 1234; Fax: ++254-(0)20-762 3927; E-mail: [email protected]. Curtis J. Richardson (E-mail: [email protected]) is an ecologist at the Nicholas School of Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708. His research has focused on wetland restoration and on wetlands as nutrient sinks and transformers. Najah A. Hussain is an aquatic ecologist on the faculty of the College of Science, University of Basrah, Basrah, Iraq. Tel: 417 730/410 958.

Peer reviewed publications: Richardson C. J., and N. A. Hussain. 2006. Restoring the Garden of Eden: an ecological assessment of the marshes of Iraq. BioScience 56: 477 – 389.

Lawler A. 2005. Reviving Iraq’s wetlands. Science 307: 1186 – 1189.

Richardson C. J., Reiss P., Hussain N. A., Alwash A. J., and Pool D. J. 2005. The restoration potential of the Mesopotamian marshes of Iraq. Science. 307:1307 – 1311.

Not peer reviewed: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2006. Back to life: environmental management of the Iraqi marshlands.

Beeston, R. 2005. Eden blossoms again on land Saddam tried to kill. The New York Times, From in Baghdad, August 25, 2005.

Websites: UNEP 2007: http://www.unep.or.jp/ UNEP 2007: http://marshlands.unep.or.jp/ http://www.tve.org/news/doc.cfm?aid=1806 http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/iraq/article558807.ece