Overview

Started in 1996 as the original Plan Vivo project, Scolel té (“the tree that grows” in the Tzeltal and Tojolobal Mayan dialects) pays members of rural communities in the Mexican state of Chiapas to plant trees and restore stands of forest in order to create carbon sinks that offset some of the gases causing global climate change. Farmers decide what species to plant and where to plant them, and then they make a proposal–in the form of a Plan Vivo (or “working plan”)–to project managers. Once approved, their plan entitles them to funding from the Scolel té Trust Fund to cover the cost of supplies; and they also receive technical assistance for baseline monitoring, planting, and follow-up monitoring. Companies, individuals or institutions wishing to offset greenhouse gas emissions can then purchase voluntary emission reductions (VERs) via the Trust Fund, the Fondo BioClimatico. A percentage of the proceeds from these sales goes directly to the participating farmers.

Quick Facts

Project Location:

16.7569318, -93.1292353

Geographic Region:

Latin America

Country or Territory:

Mexico

Biome:

Tropical Forest

Ecosystem:

Tropical Forest - Coniferous

Area being restored:

13,000 hectares

Project Lead:

Scolel té

Organization Type:

Other

Project Partners:

The Edinburgh Centre for Carbon Management

Location

Project Stage:

Implementation

Start Date:

1996-07-16

End Date:

1996-07-16

Primary Causes of Degradation

Agriculture & Livestock, Deforestation, Mining & Resource ExtractionDegradation Description

Over the past 20 years, the population of rural Chiapas has grown by 4 per cent a year, due in part to rapid immigration, and this has put tremendous pressure on the region’s natural resources. In the highlands, forests have suffered from timber extraction, charcoal burning, and overgrazing; while large areas of tropical forest in the lowlands have been cleared to make way for cattle pastures. Land degradation and a scarcity of forest products are now causing serious hardship for many communities.

Project Goals

The objective of the Scolel té project is to reliably sequester carbon through socially and environmentally responsible forest and agricultural systems that also provide sustainable livelihoods for rural communities. Another hope of project planners is that the economic benefits afforded to local participants will reduce migration from the project areas to the Lacandon “agriculture-forest frontier,” thereby helping to protect intact stands of forest from encroachment.

Monitoring

The project does not have a monitoring plan.

Stakeholders

Scolel té forestry activities are planned and undertaken by groups and communities of small farmers affiliated with local organizations such as the Unión de Crédito Pajal (a rural agricultural credit union) and The Mexican Association for Rural and Urban Transformation (AMEXTRA).

Description of Project Activities:

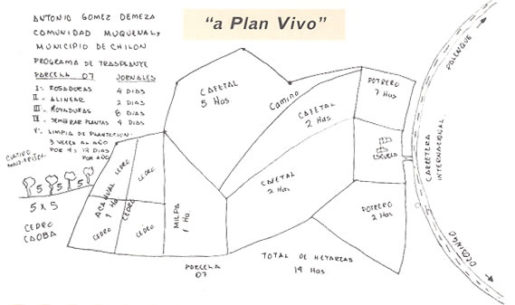

Farmers who wish to participate in the project must first draw up a management plan, called a Plan Vivo. In this plan, they decide what trees to plant and where to plant them, and they agree to make "reasonable efforts" to ensure that the systems they establish will last for 100 years. These plans are then assessed by project managers for technical feasibility, social and environmental impact, and carbon sequestration potential; and they are compared against a number of technical specifications that have already been determined with input from scientists, farmers, and technicians. Once deemed viable, plans are registered with the project's Trust Fund and are eligible to generate carbon services.

The Trust Fund provides farmers with financial and technical assistance to implement farm developments or community-scale forestry and agroforestry measures, on the basis of the carbon that will likely be sequestered. Individual farmers or forest user groups receive a 140 US$/ha planting grant in year zero and an annuity of US$ 70 for 18 years, from year 1. Technical assistance is provided in the planning and design of forestry and agroforestry systems, the construction of nurseries and propagation facilities, the collection of seeds, and the organization of activities. Baseline studies are conducted around the time of planting, and periodic monitoring continues for up to 18 years.

Native pines (Pinus oocarpa) are favoured for plantation in the uplands, and cedars (Juniperus lusitanica) in the lowlands. Frequently, farmers plant maize and food crops under the trees until the canopy closes over. Some farmers are now planting avocado, mango and other fruit trees, in addition to those species that will eventually yield saleable timber. It has been estimated that tree plantations established on pastureland will increase carbon storage by approximately 120 tones per hectare. Similarly, those agro-forestry projects that intersperse timber and fruit trees with annual and perennial crops sequester about 70 tones per hectare. The full restoration of degraded forests can increase storage by about 120 tones per hectare, while the protection of threatened forests can prevent emissions of up to 300 tones per hectare.

Ecological Outcomes Achieved

Eliminate existing threats to the ecosystem:

Thus far, more than 700 individuals in 40 communities have signed up to participate in the project, and over 700 hectares of trees have been planted.

Socio-Economic & Community Outcomes Achieved

Economic vitality and local livelihoods:

This project is about more than planting trees. Scolel té is simultaneously helping to restore a degraded environment and improve the quality of life for Mayan villagers. In Yaluma, for example, farmers are planting pines on denuded hillsides. Already, they say, the trees are helping to reduce erosion and improve the soil. As much as 60% of carbon revenues from intercropped systems and enriched fallows have gone directly to farmers and have been used by them to cover establishment costs, to purchase food and medicines, and to improve their houses (Tipper, forthcoming; Nigel Asquith, unpublished data). The farmers believe the plantations will eventually provide them a steady supply of saleable timber, as well as fruit, medical plants and modest quantities of fuelwood. This should help to take pressure off of existing forests and thereby help preserve biodiversity in the region.

Key Lessons Learned

Under the Kyoto Protocol of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, governments and polluting companies in the developed world can achieve emission reductions by funding certain types of afforestation and reforestation schemes in the developing world. The instrument for this, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), has been hugely contentious, not least because many fear that such schemes could lead to the loss of natural forest and benefit large plantation companies rather than small farmers. However, small-scale projects like Scolel té show that it is possible to contribute to the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol in a way that delivers environmental benefits and at the same time, improves local livelihoods.

The Plan Vivo system pioneered in Chiapas is currently being tested in southern India and Mozambique. Evidence suggests that active carbon-trading systems can be established on a small scale and function with relatively few resources. The Edinburgh Centre for Carbon Management, joint managers of Scolel té, believes that the participatory approach has meant that farmers and communities who have signed up to join the project have devoted much more effort to planning their activities than was the case with previous state-funded forestry schemes.

Sources and Amounts of Funding

Currently, the Trust Fund set up as a clearing house for carbon credits–referred to as voluntary emissions reductions (VERs)–is selling carbon at $12 per tonne, two-thirds of which goes to the farmers. Sales of VERs in 2002 amounted to around $180,000. The main buyer was the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA Foundation), which purchased over 13,000 tonnes of carbon credits to offset the emissions spewed into the atmosphere by Formula One racing and the World Rally Championship. Other purchasers included: The Carbon Neutral Company, on behalf of a number of companies including the World Economic Forum, D’Ieteren-Audi and Pink Floyd; the World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID).

Other Resources

Dr. Richard Tipper

The Edinburgh Centre for Carbon Management

(ECCM)

Unit 2, Tower Mains Studios

18 Liberton Brae

Edinburgh EH16 6AE

Scotland, United Kingdom

Phone: +44 (0)131 666 5070

Facsimile: +44 (0)131 666 5055

Email: [email protected]

URL: www.eccm.org

Scolel Te

http://www.eccm.uk.com/scolelte/

Plan Vivo

http://www.planvivo.org/